The impact of US-China trade war on US equities

How to navigate the impact of the US-China trade war on your clients' portfolios

The US-China trade wars have been going on since late last year, with tit-for-tat tariffs applied on imports going to and from China and the United States.

Many have wondered whether it is all just attempts by president Trump to make himself look bigger in the eyes of the world - and his voter base.

But previous presidents have attempted to bring China to the table to discuss pressing issues as the rising super power becomes an established, and mature player in the world economic order.

As the world's two biggest countries try to reach a deal over the future ground rules on trade between them, this has inevitably had a consequence in the short-term on their respective economies.

Farmers in the US, for examples, are being hit by tariffs, and other companies are inevitably feeling a squeeze on sales, as their goods become more expensive.

What does this mean for investors? While the global economy may be slowing, a good number of investors are exposed to the US stock market, and therefore need to take a view in how to manage their portfolios in the coming months.

Investing in large-cap US equities is best insurance

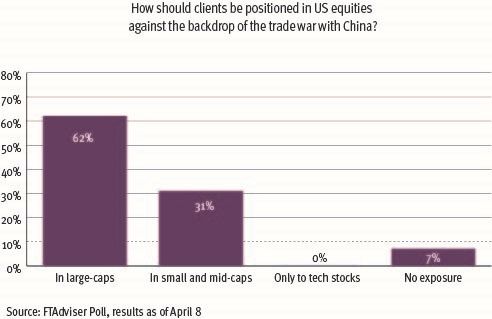

More than half of advisers think investing in large-cap US equities is the best strategy to protect their clients' portfolios from growing trade tensions, according to the latest FTAdviser Talking Point poll.

The poll asked advisers: "How should clients be positioned in US equities against the backdrop of the trade war with China?"

Some 62 per cent of advisers said their clients should invest in large-cap companies.

Almost one third (31 per cent) of advisers recommended their clients to invest in small and mid-sized cap stocks.

Only 7 per cent of advisers said their clients should have no exposure to US equities at all.

Not a single adviser recommended their clients to invest in US tech stocks.

A mid-cap is a company with a market capitalisation between $2-$10bn (£1.5-£7.6bn) and a large-cap is any company that has a market valuation of more than $10bn.

Jason Hollands, managing director of business development and communications at Tilney Investment Management, said: "Large-cap stocks represent around 75 per cent of the total US equity universe by market capitalisation and many advisers use S&P 500 tracker funds for US equity exposure.

"So it comes as no surprise that most have indicated a preference for owning large-cap US stocks as this is effectively the default position."

Large-cap stocks represent around 75 per cent of the total US equity universe by market capitalisation

Trade tensions between the world’s two largest economies have been bubbling on since last year although the countries reached a truce and held talks in January this year. Further discussions will resume next week.

Paras Anand, head of Asia-Pacific asset management at Fidelity International, said: "A détente between the US and China on global trade should be welcomed but investors would be wise not to attach too much significance to it in the context of the future direction of markets."

Ricky Chan, director and chartered financial planner at IFS Wealth and Pensions, said he was surprised by some of the respondents saying they wanted to have no exposure to the US.

But he shared the view that advisers would not recommend tech stocks, saying they prefer a more diversified approach to investing.

He added: "So this means that either they leave those decisions down to the active fund managers or, for advocates of passive funds, simply invest according to indices – both options may well include tech stocks but are not directly [down] to the financial planner’s decision."

But Mr Hollands flagged that advisers may be reluctant to recommend US equities because of fears of a recession rather than due to trade tensions.

Last month, the US yield curve inverted for the first time since 2007. The curve indicates return on yield for bonds with different maturities.

An inverted yield curve has been a bellwether for predicting every economic recession since World War Two.

Mr Hollands said: "If the US economy can keep growing until June, the current expansion phase will be the longest on record [but] everyone knows that nothing lasts forever and there are signs of slowing growth including a softening of US factory orders."

He added: "Investors have therefore become increasingly fixated on when the next US recession is due and whether the earnings cycle has peaked."

CPD: How the China US trade war is affecting US equities

Words: Dave Baxter

Images: Fotoware

What investors need to know about investing in the United States

A trade war between the world’s two largest economies is, without doubt, unhelpful for asset prices around the world, and last year’s performance figures back this up.

The Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite, for one, was down by more than 24 per cent for 2018 in sterling terms.

The damage caused by the trade dispute was not limited to China.

Emerging markets, whose performance is strongly influenced not just by global growth rates but by trade conditions around the world, saw equity prices tumble.

The MSCI Emerging Markets index lost nearly 10 per cent over 2018 in sterling terms, according to FE Analytics.

While the trade war that broke out between China and the US was not the only factor behind a difficult year for equities, it certainly contributed to severely negative investor sentiment.

US stocks – which continued to lead equity markets in 2018 – were not immune from this headwind.

On a headline basis, US equities fared much better than their counterparts.

While Chinese stocks were among 2018’s worst performers, US markets looked relatively unscathed at a glance.

The S&P 500, for example, made a small loss of 0.41 per cent in sterling terms.

That stands in contrast with significant losses not just for Chinese and emerging market equities but elsewhere, too: the MSCI World index, which has a hefty exposure to US markets, was down by around 3 per cent, while the FTSE 100, FTSE Europe ex UK and Japan’s Topix index each lost at least 8 per cent in sterling terms.

The S&P 500’s 0.41 per cent loss represented the worst year for that index since the financial crash

However, in context the US equity market struggled more than it seemed to.

The S&P 500’s 0.41 per cent loss represented the worst year for that index since the financial crash: in seven of the nine calendar years before 2018, the S&P 500 returned at least 8 per cent, and sometimes substantially more, for a sterling investor.

In the final quarter of 2018, when markets racked up the lion’s share of their losses for the year, the S&P 500 dropped by more than 12 per cent.

It is also worth noting that the second half of 2018 more broadly – a time when an escalation of the trade war, among other problems, started to worry investors – was tough for US equities, if less so.

Over this period the S&P 500 lost around 4.5 per cent. It was only the gain of a similar amount in the first half of the year that saved investors with US equity exposure from a bigger loss for the year.

Is the trade war to blame?

The status of relations between US and China has had a clear impact on the world’s biggest equity market.

From last year to now, US indices have often drifted up or down according to the outlook for trade between the two countries.

The US put levies on some $250bn of Chinese imports last year, with plans to up the tariffs on $200bn of that in January 2019, from 10 per cent to 25 per cent.

President Trump also looked at extending levies to other imports from China. Beijing has since hit back with its own round of tariffs on US goods.

However, talks have since resulted in a delay of that further escalation, with hopes that the two countries can bring about a fuller resolution of the dispute.

Notably markets have recovered as the US and China have showed signs of reconciliation, with equities in the US and elsewhere rallying strongly into 2019.

As of 19 April, the S&P 500 was up by nearly 13.5 per cent year to date.

So the trade war has likely had a significant impact on US equity valuations.

But things are not that simple: those trying to judge how attractive the market looks based on the progress of talks between the US and China would do well to remember that it remains impossible to know exactly what is driving markets.

In this case it can be particularly difficult, because several other factors have had a notable impact on investor sentiment, towards the US and more generally.

Investors have generally been skittish about US stocks for some time, given that they have performed well for many years and assets prices have looked worryingly high for some.

On a similar note, investors have become worried about global growth and the prospect of it slowing down, as well as the idea that US corporate earnings peaked last year on the back of tax cuts introduced by the president.

More substantially, the sell-off that occurred in the final quarter of 2018 – driving much of the bad performance for that year – can be attributed, at least in part, to concerns about monetary policy.

The sell-off coincides with hawkish comments from the Federal Reserve about the future path of interest rate rises.

On the same note, this year’s market recovery comes after the Federal Reserve backed away from this aggressive stance, marking a more accommodative approach.

All of this means that the impact of the trade war on US equities remains difficult to judge, because it is just one of a few factors behind the big market moves witnessed over the last year.

Trade tensions are just part of an increasingly tangled web of factors that have contributed to the dominant negative sentiment

Jasper Lawler, head of research at London Capital Group, noted last year that investors should consider the trade war, but also look at the wider context to explain moves in the equity market.

“Trade tensions are just part of an increasingly tangled web of factors that have contributed to the dominant negative sentiment,” he says.

“It’s easy to put the blame squarely on the brewing trade war; it contributed to global growth concerns and fanned fears over a slowdown in China, potentially hitting future demand for oil.

“However, the fact is that deleveraging in China meant cracks were showing in the economy well before trade tensions escalated.”

He adds that Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell’s more dovish comments, beginning late last year, proved a “gamechanger”, meaning trade talks have not been alone in lifting markets.

US stocks that rely more heavily on global trade do look more vulnerable than domestically oriented names.

In March, John Butters, an earnings analyst for data specialist FactSet, noted that those S&P 500 companies generating more than half of their sales from outside the US were expected to underperform their more domestically focused peers over the Q1 earnings season.

But again, it is important to note that trade tensions are among a number of factors expected to hit earnings.

What now?

Investors now need to assess the future impact of trade relations between the US and China, from the effect of the tariffs put in place last year to the attempts to reach a resolution.

As noted, the narrative of the trade war arguably helped to fuel the sell-off late last year, in combination with other factors.

Respected organisations such as the World Trade Organisation have even warned that “tensions” would severely hinder global trade over the next two years.

However, the idea that global trade hinges on the resolution of such tensions is not shared by all.

Some commentators are sceptical about whether the tariffs placed on Chinese goods sold into the US have done much at all to dent global trade.

In a note realised in April this year, Capital Economics claimed that while global trade had contracted by the biggest amount since the financial crisis in the final quarter of 2018, the dispute between the US and China was not the root cause.

“A detailed breakdown of global exports suggests that the US-China trade war cannot be blamed for the slowdown in world trade,” the note says.

“Instead, the underlying slowdown has featured a wide range of goods, with a drop in exports of electricals and materials causing growth to slow especially sharply in recent months.”

The firm added that the slowdown in trade had been “broad-based” in terms of geography, suggesting it did not stem from the recent dispute.

As such, an argument can be made that while trade is slowing, this is down to other factors such as the slowdown in China’s economy.

A detailed breakdown of global exports suggests that the US-China trade war cannot be blamed for the slowdown in world trade

As such, tariffs have arguably had little real impact on global trade.

And as Capital Economics notes, this suggests that any lasting deal between the US and China is “unlikely to precipitate a turnaround in world trade”.

If this argument holds up, the current trade talks between the US and China will do little in terms of their effect on investment fundamentals globally.

That, in the medium term, means that the global slowdown and other problems facing investors could continue.

That said, there are also positive aspects of a thaw in the trade war. For one, China has been investing in the US as part of a gradual improvement in relations.

Any continuation of this, and improvement in trade terms between the two, could boost earnings from US companies, which tends to be one major driver of the US stockmarket.

A deal between the US and China could help to improve investor sentiment more generally, which can have a significant effect on markets.

The nitty gritty

Another question, however, is whether the issues between and US and China can be resolved.

There are several reasons for tension to exist between the two, from US concerns about China keeping its currency artificially low to competition in the technology space.

If a deal is agreed, it may help the two economies to co-operate for longer, which would benefit companies on both sides. But two key areas of difficulty remain.

Firstly, after decades of US economic dominance, tensions will continue to arise from the fact that China is now catching up, and growing ever more influential.

As the US seeks to defend its own sphere of influence, this could create further disputes.

Secondly, and more specifically, both countries are attempting to become dominant in the technology space, which has led both the US equity market and global markets in recent years.

Any trade deal, while positive for markets, is unlikely to create a lasting resolution for these problems.

House View: Emerging markets also affected by trade wars

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index, a measure of emerging markets equities, was down 14.3 per cent in 2018, but this masked a considerable dispersion of returns, particularly in US dollar terms.

Turkey was the year’s worst performer, thanks to a collapse in the lira, with equities losing investors 57.6 per cent in dollar terms.

The best performing major market, Brazil, was still down for the year, but only just at a less painful 0.2 per cent.

The outlier was Qatar, where the equity market rallied 29.8 per cent, despite the ongoing economic blockade by regional countries.

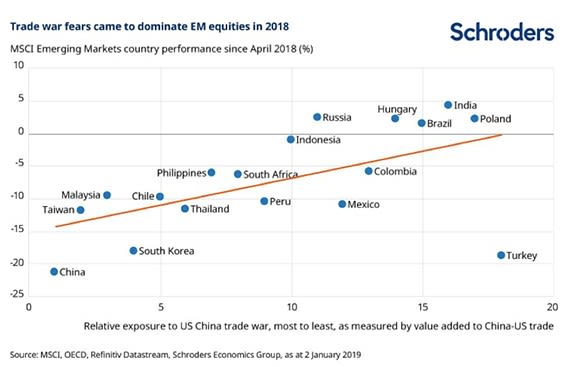

The dominant common theme for emerging markets equities in 2018 was trade wars, as demonstrated by the chart below.

Craig Botham, Emerging Markets Economist, explains: “Taking April, when the US first mooted China-specific tariffs, as a starting point, there is a striking correlation between equity performance in EM and a country's exposure to the US-China trade war, as measured by value added to China-US trade.

“The less exposed economies managed to eke out small positive price gains, but due to currency moves still saw a negative overall return in dollar terms.”

...but are emerging markets set to rebound in 2019?

After a challenging 2018, could EM equities recover this year? Expectations for major global central banks to take further measures to tighten monetary policy, and the impact of the US-China trade dispute will not help.

However, Keith Wade, chief economist at Schroders has named the return of emerging markets as one of his themes for the year.

He said: “If our forecast is correct and the US Federal Reserve decides to end its interest rate tightening cycle in June 2019, there is a good argument to be made for the dollar to weaken.

“ This would relieve the pressure on dollar borrowers and emerging markets. Arguably, those markets may already be discounting the worst, with both equities and foreign exchange having fallen significantly.”

Macroeconomic developments will be important, and it may be that further stimulus in China is the catalyst for investors to return to the region.

Mr Wade believes this would help to alleviate concern over another collapse in global trade as seen in 2007-08.

Wade added: “Whilst US-China trade will slow, unless the trade war goes global there is no reason to expect an out

Andrew Rymer is an investment writer at Schroders